A Model for a Life Well-Lived

Lately, I’ve been reflecting on how different areas of my life such as work, health, relationships, personal growth, leisure, and contribution interact with one another. When we over-focus on one, others quietly shrink. And sometimes it’s only after months or years that something feels off.

Interestingly, around the same time, I had been building scoring models at work, trying to combine many noisy signals into a clearer picture. The goal was to understand complex entities by weighting multiple sources of information into something coherent and useful. That experience made me wonder: could I apply the same mindset to life itself?

What if we could combine the “signals” of how we spend our time: career, relationships, health, and more into a single picture of fulfillment? Could we model a well-lived life?

This post is my attempt to do that. It’s part framework, part experiment, a way to explore whether our effort is actually going to the places that matter most.

Utility: The Happiness Behind Our Choices

The concept of utility comes from economics. It traditionally refers to the value or satisfaction a person derives from consuming a good or service. But the idea is much more flexible than it sounds.

Utility isn’t just about price tags or consumption , it’s about what makes an action or decision worthwhile. In this post, utility becomes a way to quantify something far more personal: happiness. Not just momentary pleasure, but holistic life fulfillment. This includes growth, meaning, relationships, challenge, and well-being.

So when we say happiness utility, we’re referring to the cumulative satisfaction you derive from how you spend your time across different life domains. It’s about making sense of where your hours go and whether those hours lead to the life you actually want.

Diminishing Returns and Marginal Utility

One of the most important ideas in this model is marginal utility which is the additional benefit you get from putting in one more unit of effort. At first, the returns are big. But over time, they shrink. This concept is called diminishing returns.

Let’s take a generic example: Imagine you’re learning a new language. The first 10 hours might let you master greetings, basic vocabulary, and simple phrases, a huge leap. But going from 200 hours to 210 hours? The difference might be barely noticeable unless you’re pursuing fluency or refinement.

This concept isn’t meant to suggest that pushing for mastery or excellence is always a bad idea. In fact, in many areas of life especially in relationships or professional work, the last 10% of effort can matter a lot. Finishing strong, being consistent, and going the extra mile can lead to deep, meaningful impact. But marginal utility reminds us to be deliberate: that extra effort comes with opportunity costs.

Now let’s look at how this plays out in life:

In work: Compare working a 40-hour week to pushing 90 hours. The first 40 hours likely bring high returns such as focused output, growth, income. But those extra 50 hours? They often add stress, eat into sleep and relationships, and only slightly increase your results. The marginal utility per extra hour drops steeply.

In relationships: Meeting your friends once a week might maintain a healthy connection. Adding a second call could deepen the bond. But meeting them three times a day? Eventually, it provides little added value and may even reduce novelty or appreciation.

Understanding marginal utility is about recognizing when the next hour you spend is better used somewhere else. It’s the shift from “Is this productive?” to “Is this still worthwhile?”

Modeling Happiness Utility

To bring structure to this idea, I designed a simple mathematical model that evaluates happiness utility based on two key inputs: how much time you spend on a domain, and how important that domain is at your current stage in life.

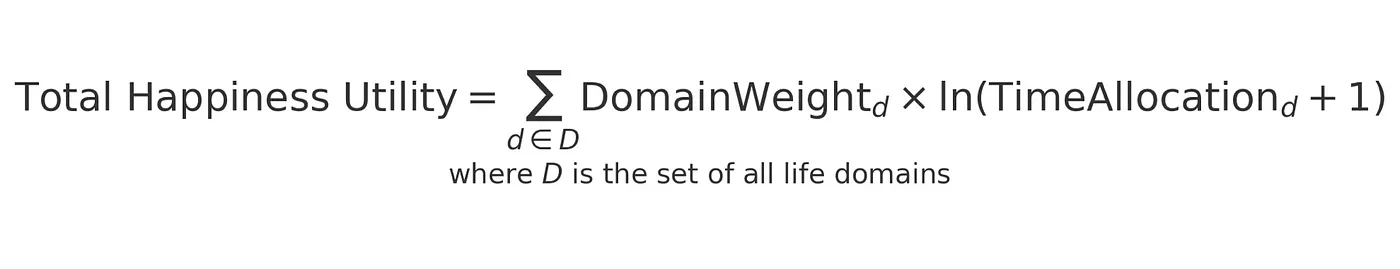

Here’s the formula:

Let’s unpack it:

Time Allocation: This is how much effort or attention you give to a domain, whether that’s hours worked, days spent with family, or evenings dedicated to hobbies. It’s a proportion of your available time.

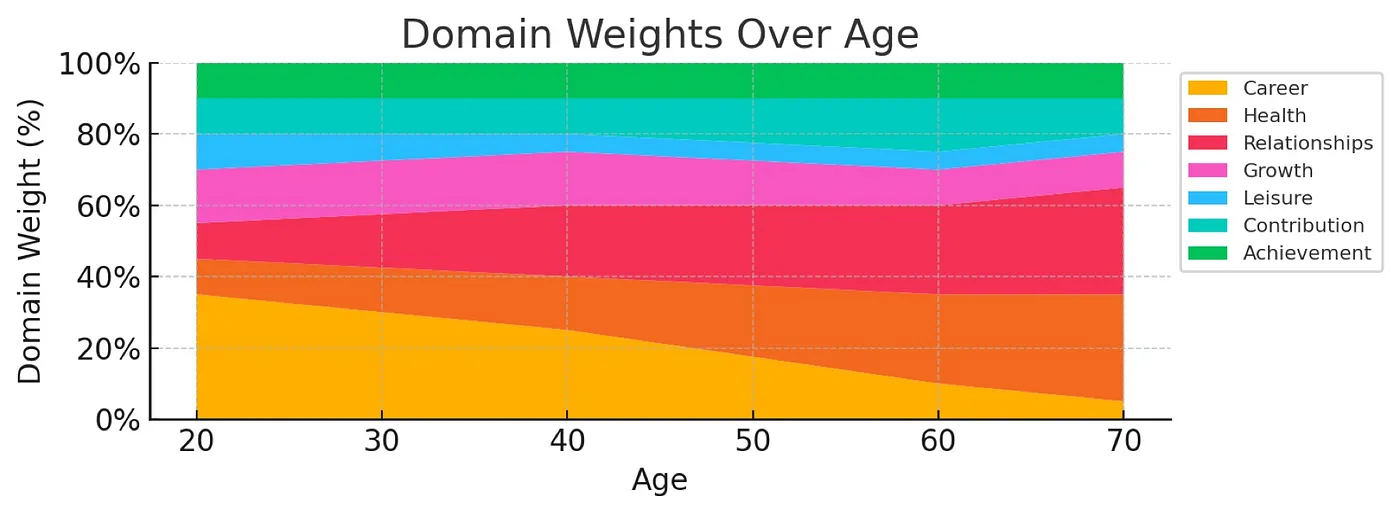

Domain Weight: Not all life areas are equally important at all times. In your 20s, career might be more heavily weighted. In later life, health and relationships might take center stage. Domain weight adjusts for those changing priorities.

ln(Time + 1): This logarithmic function captures diminishing returns. It ensures that early investments in a domain yield large gains in utility, but adding more time eventually flattens out. (We add 1 to handle zero allocation without undefined values.)

Why use a model at all? Because life decisions are messy. This formula isn’t meant to calculate a perfect answer, it’s meant to provide intuition. It lets us visualize trade-offs: whether we’re overinvesting in work and underinvesting in health, or vice versa. It helps us ask better questions.

Are we allocating time in ways that actually bring us fulfillment? Are we giving too much to things that no longer move the needle?

This is the core premise of happiness utility: that intentional time allocation, weighted by what matters most to us now, can help steer life toward a more meaningful trajectory.

Life’s Core Domains

To make the model concrete, I defined seven core domains that broadly capture where our time and energy tend to go. Each one plays a different role in shaping a fulfilling life.

Domains Definision

Career: This includes your professional life, income, intellectual stimulation, mastery, and external achievement. Career provides structure, resources, and often identity, especially in early adulthood. For many, it’s the main way to generate financial stability and a sense of growth.

Health: Not just physical health, but also mental and emotional well-being. It includes sleep, exercise, diet, and stress management. Health is foundational since it affects energy, resilience, and even how we experience joy or handle setbacks. Its importance tends to grow with age.

Relationships: Deep and meaningful connections with family, friends, partners, and community. Relationships give life emotional texture and support. They often don’t deliver immediate, measurable outcomes, but they are essential to long-term fulfillment and resilience during life’s inevitable hardships.

Growth: Intellectual and personal development. This domain includes learning new skills, exploring curiosity, reading, creative projects, and self-reflection. Growth keeps us mentally agile, engaged, and adaptable, and often enhances other domains indirectly.

Leisure: Recreation, fun, entertainment, travel, and downtime. Leisure recharges us and brings joy, novelty, and play. Though often underrated, it contributes to mental health, creativity, and connection with the world in unstructured ways.

Contribution: Acts of service, giving back to others or a community, mentoring, or creating something of value beyond personal gain. Contribution provides purpose, legacy, and a sense of impact. It tends to matter more as we mature and seek meaning beyond self-interest.

Achievement: Long-term accomplishments and life goals, often the culmination of effort in career, learning, or personal projects. It represents the results of intentional work: financial freedom, recognition, completed journeys. While achievement often overlaps with career, it’s broader because it includes other things such as publishing a book, raising a child, or running a marathon.

These domains are not mutually exclusive, and they often reinforce one another. For example, investing in health can improve work performance, and strong relationships can support personal growth. But because time is finite, the goal of the model is to make trade-offs visible so we can navigate life more deliberately.

How Domain Importance Shifts Over Time

This chart illustrates how the importance of each life domain shifts as we age. From our 20s to our 70s, what contributes most to our overall fulfillment changes in predictable ways. Career takes up the largest share early on as we focus on building skills, income, and professional identity. Over time, its relative importance declines, making space for domains like health and relationships, which steadily grow in value as physical well-being and emotional connection become more central. Growth remains steady throughout, while leisure holds a consistent but modest slice, important but rarely dominant. Contribution becomes more important in midlife, reflecting a growing desire to give back or find purpose beyond oneself. Achievement stays relatively constant, representing the long-term payoff of goals reached over decades. Understanding how these weights evolve provides the foundation for better time allocation decisions across life stages.

Life Strategies: Definitions and Key Differences

To explore how different approaches to time allocation affect life fulfillment, I modeled four common strategies. While some may seem similar at a glance, their structure, timing, and assumptions create meaningful differences in long-term happiness utility.

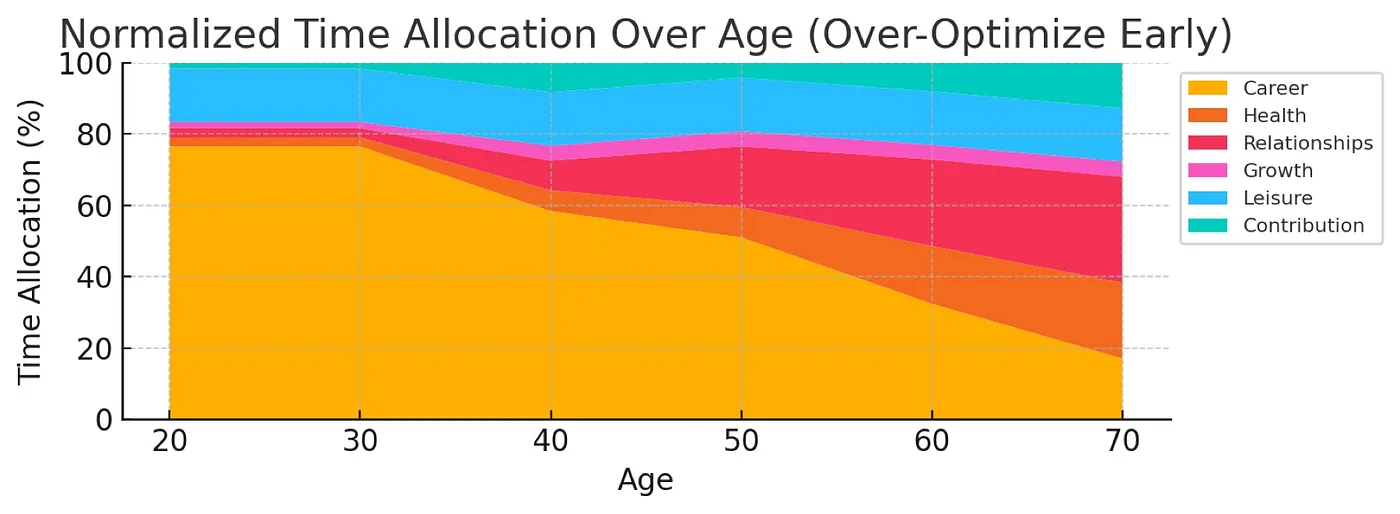

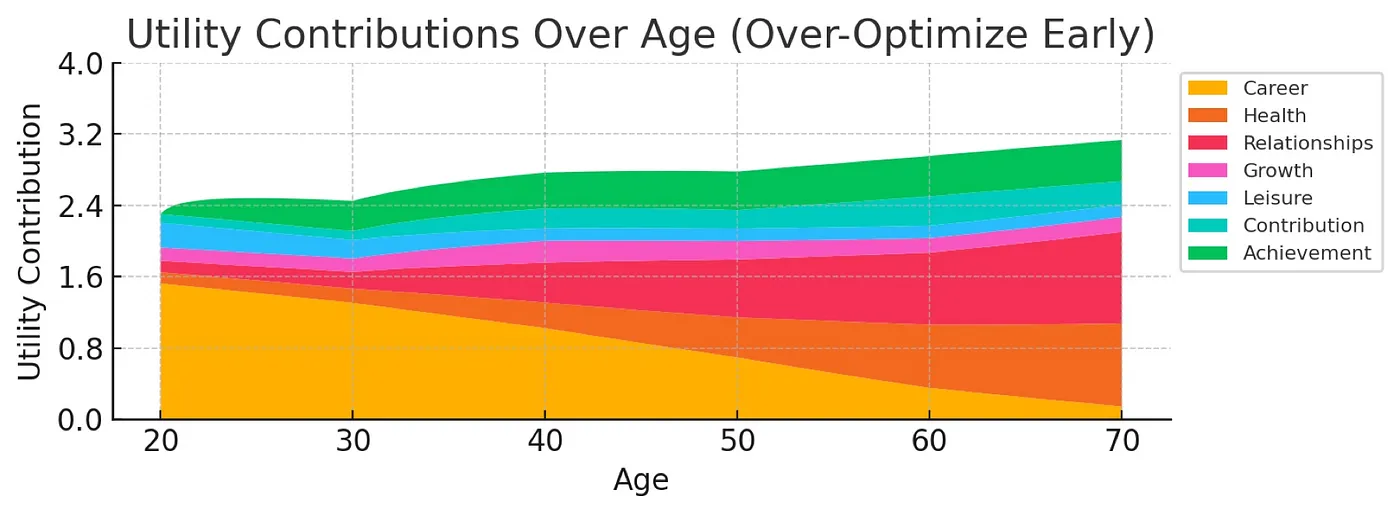

Strategy 1: Over-Optimize Early

This strategy allocates the majority of time and effort into career and achievement domains early in life. The idea is to “front-load” success: accumulating resources, status, or freedom early on with the hope of enjoying the benefits later.

Key Traits:

- 70—80% of time spent on career and achievement during youth

- Minimal early investment in relationships, health, or leisure

- Career utility peaks quickly, then plateaus

- Later life suffers due to underinvestment in rising-weight domains

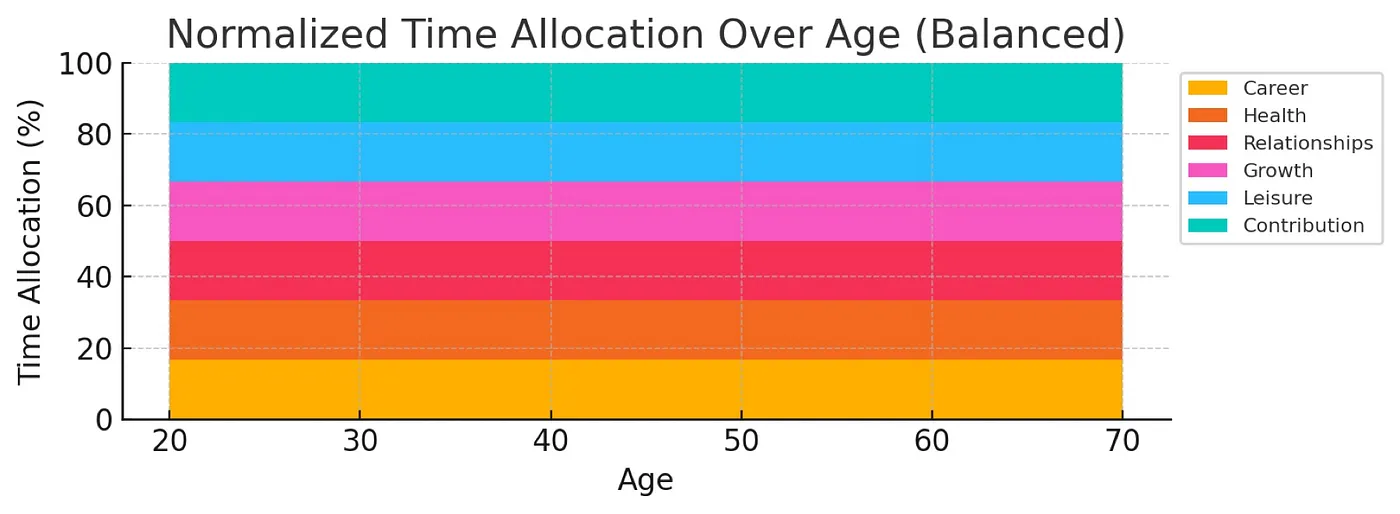

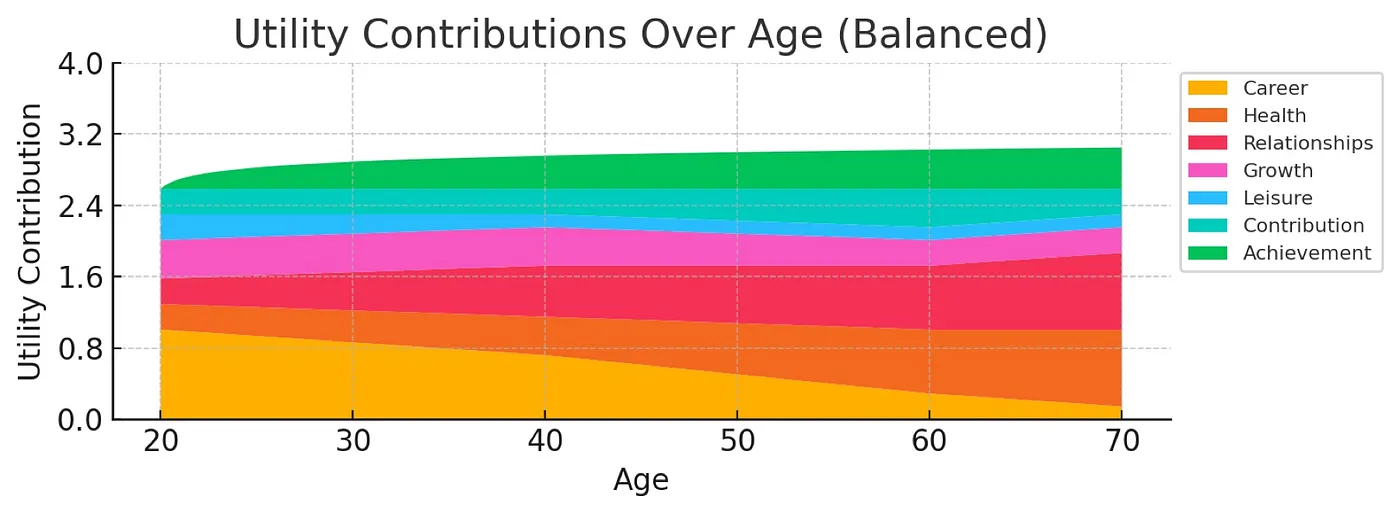

Strategy 2: Balanced

Balanced spreads time relatively evenly across all domains throughout all life stages. It values present-day satisfaction and long-term stability by avoiding overcommitment in any single area.

Key Traits:

- Equal time allocation across domains at all ages

- Moderate but stable utility from all areas

- Health, relationships, and contribution steadily grow

- No sharp dips or spikes, resilient to setbacks in any one domain

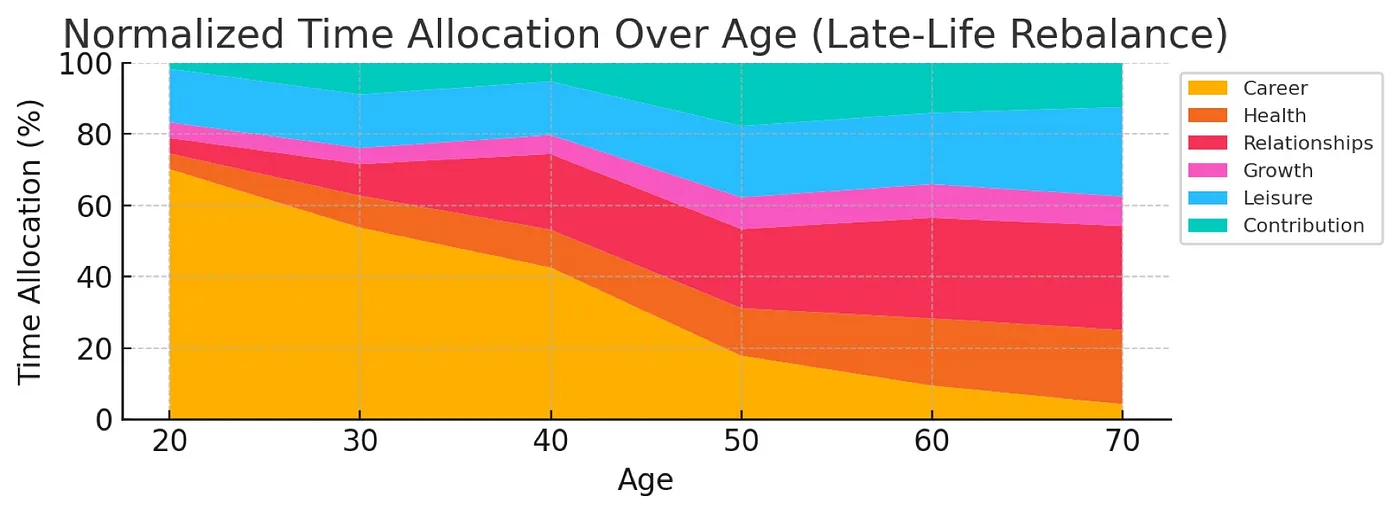

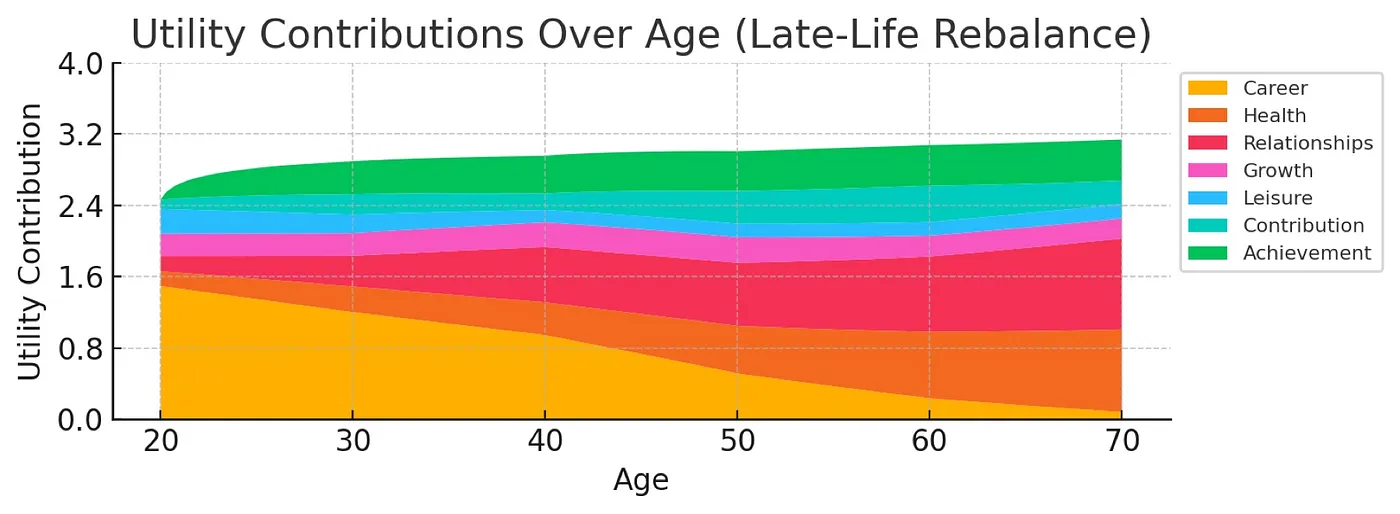

Strategy 3: Late-Life Rebalance

This hybrid strategy starts like Over-Optimize Early, with strong early investment in career. But around midlife, it intentionally shifts time toward underweighted but rising domains like relationships, health, leisure, and contribution.

Key Traits:

- Career-focused in youth

- Midlife pivot toward emotional, physical, and communal domains

- Utility dips slightly during transition, then rises in later life

- Combines early success with late-stage richness

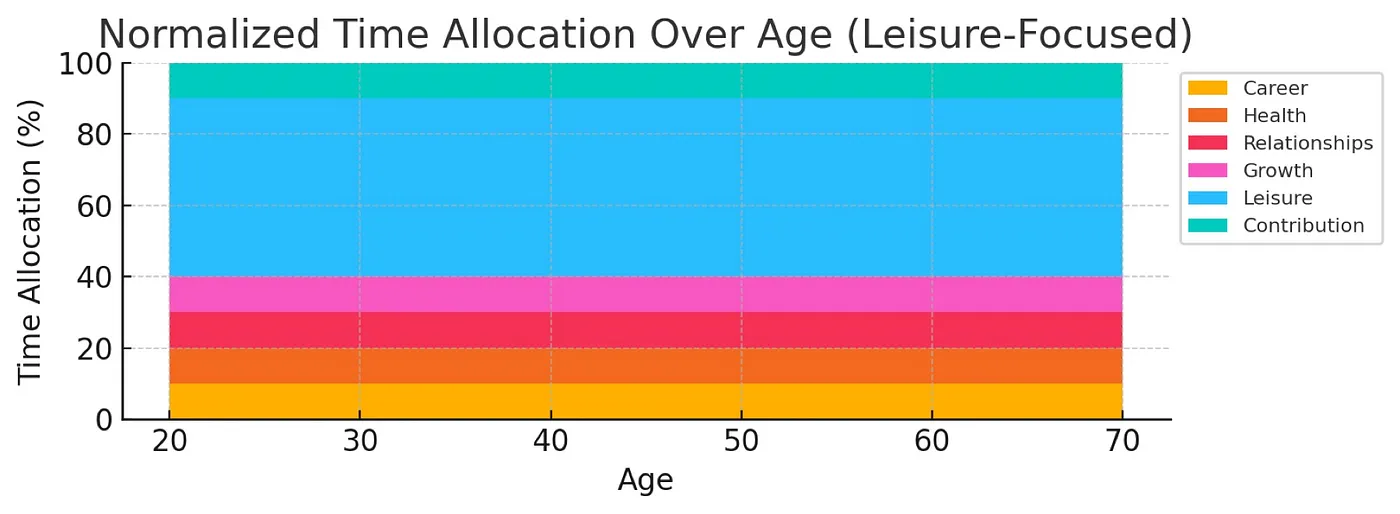

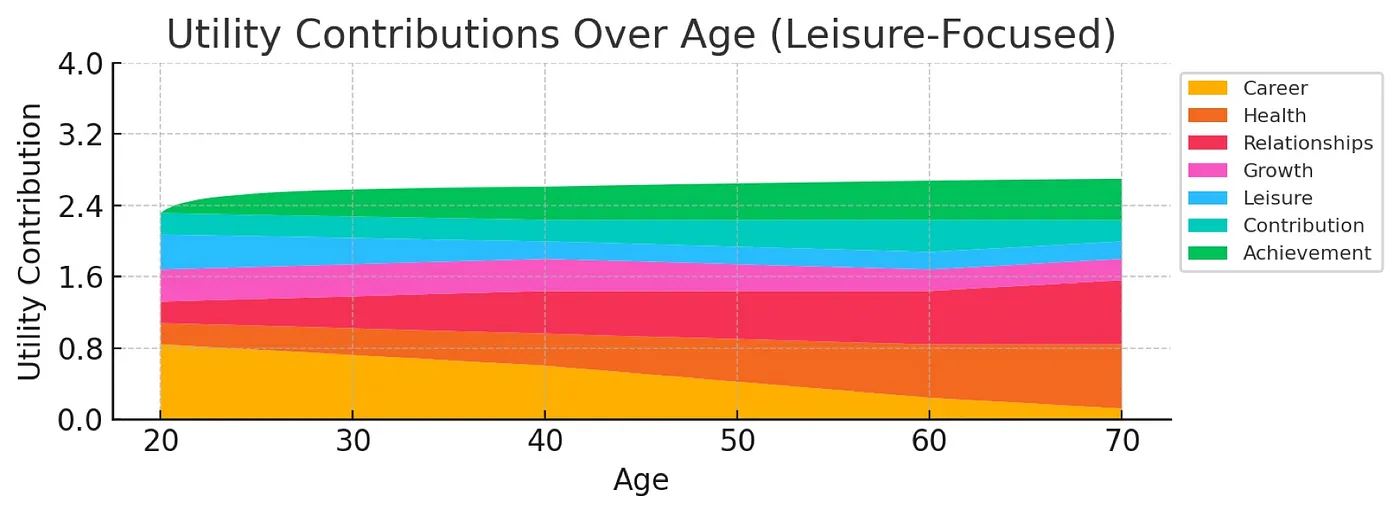

Strategy 4: Leisure-Focused

This strategy prioritizes enjoyment, rest, and freedom across all life stages. It values daily ease and flexibility over long-term achievement or contribution.

Key Traits:

- High allocation to leisure throughout life

- Lower investment in career, growth, or achievement

- Early utility is decent, but long-term payoff is limited

- May lead to stagnation or regret in later stages

Key Differences

Over-Optimize Early vs. Late-Life Rebalance: Both begin similarly, but only the latter adjusts as life changes. One stays fixed; the other evolves.

Balanced vs. Late-Life Rebalance: Balanced maintains steady allocation. Rebalance leverages domain timing with early optimization, then strategic shift.

Leisure-Focused vs. Balanced: Leisure-Focused prioritizes short-term comfort. Balanced incorporates leisure without sacrificing long-term utility.

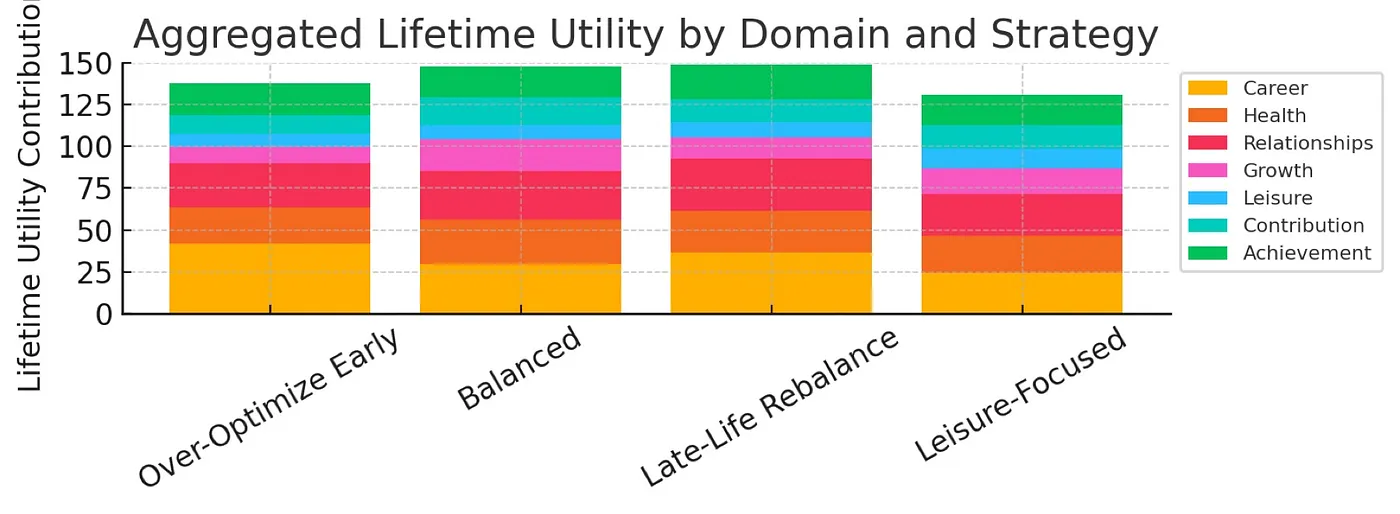

What the Simulations Showed

Over-Optimize Early

This strategy front-loads effort into career and achievement during youth and early adulthood, betting on long-term payoffs. In the simulation, this strategy shows a steep rise in utility early on, driven by rapid career growth and income accumulation.

However, the utility curve plateaus by midlife. Domains like relationships and health, which carry increasing weights as we age, were underdeveloped in earlier years and thus offer limited utility later, even if one has ample resources. The marginal returns diminish, and there is little rebound in total happiness despite strong career success.

Balanced

Balanced shows a steady, moderate curve across all domains and all life stages. It never peaks dramatically, but it also never crashes. Utility contributions are spread evenly across the domains, making this strategy resilient to life changes.

This strategy performs especially well in long-term health and relationships, which grow steadily and compound over time. While it may miss some early high-reward opportunities in career or achievement, it provides a reliable and fulfilling baseline throughout life.

Late-Life Rebalance

This strategy combines the high momentum of early career focus with a thoughtful pivot. It resembles Over-Optimize Early in youth, but starting around midlife, it gradually reallocates time into health, relationships, leisure, and contribution.

This pivot aligns well with the increasing domain weights of these areas later in life. As a result, the utility graph dips slightly in transition but rebounds significantly in older age and eventually outperforming all other strategies in cumulative lifetime utility.

Leisure-Focused

This strategy prioritizes enjoyment, relaxation, and freedom across all ages. It delivers decent utility in leisure-related domains early in life and maintains a laid-back trajectory. However, because it neglects higher-weight domains like career, growth, and contribution, it falls short on long-term utility accumulation.

The result is a curve that starts soft and flattens quickly. Without strong investment in domains that yield compounding utility, this strategy underperforms in middle and later stages of life.

Comparative Summary

In terms of total lifetime happiness utility:

Late-Life Rebalance comes out on top by leveraging compounding effects in both early and late stages.

Balanced closely follows with minimal risk and consistent satisfaction.

Over-Optimize Early starts strong but cannot sustain utility over the long run.

Leisure-Focused offers early gratification but has the lowest lifetime aggregate.

Each strategy reveals different trade-offs. Depending on personal values, circumstances, and goals, one may be more appropriate than the others. The point isn’t to prescribe a “best” life, but to invite more conscious choices about how we live it.

Reflections & Takeaways

We often don’t realize we’re pursuing a “strategy” at all. We just respond to expectations, habits, or fear. But the time we allocate today quietly shapes the fulfillment we feel tomorrow.

Here are a few takeaways that stuck with me:

Compounding doesn’t only apply to wealth. Health, trust, love, and personal growth all benefit from consistent, early investment. The payoff isn’t always immediate, but over time it becomes irreplaceable.

Some trade-offs are necessary, but many are unconscious. The problem isn’t hard work, it’s believing it will pay off in all the ways that matter. Or that other things can always wait.

Leisure isn’t the enemy of ambition, but it can’t carry the whole load. Joyful moments matter. But when leisure crowds out deeper domains, fulfillment starts to fade.

The best strategy might be one that evolves. Life isn’t static, so our time allocation shouldn’t be either. The Late-Life Rebalance worked best because it acknowledged the changing importance of domains and adjusted accordingly.

So if there’s a question I’d want to leave with, it might be this:

Have you been pouring time into something that no longer moves your happiness forward?

Or maybe:

What domain have you quietly neglected even though it’s becoming more important to you now?

It’s not about mapping out life like a spreadsheet. But modeling it, even loosely, can be enough to spot the imbalance, or start the shift.

Because even small changes in how we spend time today can compound into a life that feels better lived tomorrow.